Since Donald Trump's election, there's been a lot of commentary and speculation on what his election means for education in general and New Jersey.

Last week the NJSpotlight looked at Trump's and Betsy Devos' records in a piece titled, "DECODING DEVOS: WHAT NEW EDUCATION SECRETARY COULD MEAN FOR NEW JERSEY." The piece focused on Trump and DeVos' support for charter schools and school vouchers:

No doubt, DeVos will bring a very pro-charter orientation to the federal Department of Education.Although the Obama administration always opposed vouchers for private schools, the NJSpotlight said it might not be that big a shift after all:

That’s hardly a big shift; President Barack Obama and his education secretaries were also supportive of charters. But a Trump administration appears to want to step that up a notch, including a possible infusion of tens of billions of dollars into the choice movement. One promise from Trump was a $20 billion grant program, although how that would work has never been detailed.

For New Jersey, that could mean some mobilization of what is already a strong charter movement of more than 80 schools and 40,000 students. A massive grant program to further expand charters or even bring back private-school vouchers could force the state to move in some novel directions.

I don't disagree with these conjectures, but I think they are missing two indirect changes which will have profound consequences for New Jersey in the realm of school budgets.

- The Abood decision will be overturned and NJ's public sector will become right-to-work. Right-to-work will disempower the NJEA and the fiscal tug-of-war between teacher interests and taxpayer interests will shift in favor of taxpayers and, arguably, students.

- The reduction of taxes on high-earners and retreat from Wall Street regulation will be an economic stimulus for New Jersey, improve the state's fiscal situation, and give the state more room to increase its own taxes.

We do not know what Trump's education budgets will look like, although I expect them to be less generous than a Democratic president's would be. It's possible that Trump will cut Title I spending, which would harm high poverty schools, although federal money for education is very small compared to state and local.

It's also possible (likely?) that Trump will lower federal payments to states, forcing states to cut services and/or compensate for the loss of federal dollars from other budget categories.

It's also possible (likely?) that Trump will lower federal payments to states, forcing states to cut services and/or compensate for the loss of federal dollars from other budget categories.

However, I think that expansionary fiscal policy through taxation and labor deregulation overturning Abood will have significant long-term effects on New Jersey school finance that should not be overlooked.

|

| Antonin Scalia's replacement will likely be part of a 5-4 decision that will disempower public sector unions. |

Abood v. Detroit Board of Education is a 1977 Supreme Court decision that said in a union-shop state (like New Jersey), public employees could still be required to pay "agency fees" even if they disagreed with the union's agenda and never wanted to be a union member.

The rationale is that since unions are required (and want to) negotiate for all employees, if certain employees did not pay "fair share fees," they would be free riders.

The Abood decision was a compromise because it said that workers could be required to contribute to negotiations, but not be required to contribute money for political activities, even in a "union security" state.

Abood was challenged from the right in 2015's Supreme Court case Friedrichs v. CTA, a case that union supporters called "a dagger at the heart of the trade union movement," although it would only affect the public sector.

(See this by Jersey Jazzman for a critical look at the Friedrichs plaintiffs and their case.)

Legal experts and unions themselves had expected the Supreme Court's five conservative majority to overrule Abood and make the entire country right-to-work for the public sector, but Antonin Scalia's death in January 2016 deprived conservatives of their majority and the Supreme Court's eventual 4-4 decision upheld a lower court decision affirming Abood and mandatory fair-share fees.

Presumably Donald Trump's Supreme Court nominee will vote with Alito, Thomas, Roberts, and Kennedy to overturn Abood when the Constitutionality of mandatory agency-fees in the public sector is re-heard. (the legal vehicle for overturning Abood is now Janus v. ASFCME, a case out of Illinois.)

The relevance of Abood to New Jersey is that the NJEA's fees for full-time teachers and other school staff are $866 per year and the NJEA has 200,000 members.

(The $866 is a constant head tax -- it does not depend on salary. That $866 amount doesn't include county and local education association fees either.)

In New Jersey, the NJEA determines that 82% of its expenses are spent on negotiations, so if a staff member wanted to not join the union, the reduction in fees would be very small, about $155. As a consequence of the smallness of the savings, 99% of eligible school staff in New Jersey are full-paying NJEA members, although I am sure that the NJEA's leadership does not have a 99% approval rating from members.

As a consequence of a 200,000 membership paying so much, the NJEA has a $160 million budget and over 1,000 employees.

Without peer, the NJEA is New Jersey's lobbying giant, easily outspending all other groups:

Labor unions — particularly the New Jersey Education Association — have dominated special interest spending on New Jersey elections over the last 15 years, according to an analysis released today by the state’s campaign finance watchdog agency.

The Election Law Enforcement Commission (ELEC) found that the state's top 25 special interest groups — which include unions, business advocacy organizations, ideological organizations and regulated utilities — spent $311 million from 1999 to 2013 on campaign contributions, independent spending and lobbying lawmakers and the executive branch.

Unions, both from the private and public sector, accounted for more than half of that, spending nearly $171 million. And of those unions, none came close to the NJEA, which represents nearly 200,000 teachers and school staff, making it the largest public workers union in New Jersey.

The NJEA has spent $57 million since 1999 – including $19.5 million in 2013 alone, when it largely propped up the underfunded and unsuccessful gubernatorial campaign of Democrat Barbara Buono.

“NJEA is considered a powerhouse in Trenton and for good reason,” wrote Jeff Brindle, ELEC’s executive director. “Few special interest groups come close to matching its financial clout,” said Brindle.

Moreover, the NJEA is also a major contributor to scores of activist groups ($553,500 to the Education Law Center, thousands to the NAACP, thousands to the Latino Institute, thousands to NJ Citizen Action), think tanks ($5,000 the Eagleton Institute of Politics, $125,000 to the NJ Policy Perspective), and completely apolitical charities (eg, Friends of Drumthwacket, the Brain Injury Alliance, Boys & Girls Clubs, Komen Breast Cancer Foundation etc etc).

(see this article about the NEA's reach)

The NJEA is the Education Law Center's biggest single contributor. Two of the ELC's twelve trustees - Vincent Giordano and Edward Richardson - are NJEA executives.

Whether or not agency fees are appropriate or constitutional, the relevant consequence for New Jersey is that if teachers were not required to pay agency fees, many would quit the union completely and pay $0 to the NJEA. Whether or not this should be called "freeloading" or a principled disagreement with the NJEA's orientation is not the point, the point is that union membership falls in a right-to-work environment.

As a former teacher myself, it is an open secret that numerous union members do not like their unions and would stop paying fees if they could. Among teachers, the discontent is always highest among new teachers, who are put at the bottom of salary scales, subject to first-firing in Reduction In Forces, and disadvantaged by the pension system's design.

As a former teacher myself, it is an open secret that numerous union members do not like their unions and would stop paying fees if they could. Among teachers, the discontent is always highest among new teachers, who are put at the bottom of salary scales, subject to first-firing in Reduction In Forces, and disadvantaged by the pension system's design.

How steep might the NJEA's membership dropoff be if the NJ public sector became right-to-work?

|

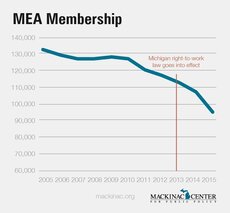

| Membership of Michigan's teacher's union has fallen since Michigan became right-to-work. |

In Wisconsin, 2011's Act 10 went much farther to disempower public sector unions than a reversal of Abood would, but teacher union membership fell from 98,000 to 40,000 from 2011 to 2015.

If 20% of NJEA members refused to join the join, the NJEA would lose over $30 million. If the NJEA's dropout rate equaled Wisconsin's, the loss of revenue would be $80 million per year.

A less well-funded NJEA would have less clout within the Democratic Party and less financial muscle to get Democrats elected. A weaker NJEA would have less money to contribute to officially non-partisan, but pro-spending, organizations such as the Education Law Center.

Although even a weakened NJEA might still fund the ELC and the ELC may not need the NJEA's $550,000 per year anyway, the NJEA's lobbying would be less likely to get the Democratic Party to heed it in areas like banning outsourcing, opposing vouchers, preserving LIFO, and increasing education aid rather than redistributing it. (the NJEA opposes Sweeney's aid redistribution plan as "divisive.") Democrats who want to reduce post-retirement health care benefits would become confident making their voices heard since the NJEA's ability to retaliate would be reduced.

Lower teacher salaries might mean that fewer highly-qualified people go into teaching, but in the short term, having to spend less on staff salaries would give districts more budgetary space than they have now and give them greater flexibility in firing decisions.

If 20% of NJEA members refused to join the join, the NJEA would lose over $30 million. If the NJEA's dropout rate equaled Wisconsin's, the loss of revenue would be $80 million per year.

A less well-funded NJEA would have less clout within the Democratic Party and less financial muscle to get Democrats elected. A weaker NJEA would have less money to contribute to officially non-partisan, but pro-spending, organizations such as the Education Law Center.

Although even a weakened NJEA might still fund the ELC and the ELC may not need the NJEA's $550,000 per year anyway, the NJEA's lobbying would be less likely to get the Democratic Party to heed it in areas like banning outsourcing, opposing vouchers, preserving LIFO, and increasing education aid rather than redistributing it. (the NJEA opposes Sweeney's aid redistribution plan as "divisive.") Democrats who want to reduce post-retirement health care benefits would become confident making their voices heard since the NJEA's ability to retaliate would be reduced.

Lower teacher salaries might mean that fewer highly-qualified people go into teaching, but in the short term, having to spend less on staff salaries would give districts more budgetary space than they have now and give them greater flexibility in firing decisions.

2. Effects of Tax Cuts

Discussing the fiscal consequences of Trumpism is more difficult than what the legal consequences will be.

New Jersey has a lot of high-earners, with 7.5% of households being worth over $1 million, the second highest percentage of millionaire households in the US.

Discussing the fiscal consequences of Trumpism is more difficult than what the legal consequences will be.

New Jersey has a lot of high-earners, with 7.5% of households being worth over $1 million, the second highest percentage of millionaire households in the US.

Any tax cut targeting the rich will disproportionately benefit New Jersey:

It's possible that the Fed's actions will end the bull market and this revenue boom may not materialize, but throughout the 1990s the stock market rose despite rate increases, so I would bet on the bull market at this point.

Also, if the mortgage-interest deduction were capped and/or the deduction for state and local taxes were reduced or eliminated, the consequences would be negative for New Jersey.

Consider that Blue States send much more money to Washington than they receive, while the reverse is true for Red States, which tend to favor Republicans. Blue States also enjoy significantly higher per capita income than Red States and are home to a disproportionate share of the nation’s highest earners. The upshot is that if the Trump administration cuts taxes on top earners as expected, the federal tax burden on Blue States will fall especially sharply. Those states will thus have new fiscal flexibility, should they choose to offset other aspects of the Trump agenda.So, if federal taxes are dropping, New Jersey's next governor and legislature might feel they have more leeway to increase NJ's own taxes.

The experience in California is reassuring. Facing budget shortfalls and cutbacks in essential public services, the state’s voters approved Proposition 30 in 2012, which raised the state’s top marginal income tax rate to over 13 percent, significantly higher than that of any other. Opponents predicted that wealthy California taxpayers would flee in droves to Nevada, Oregon and beyond.

But the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy in Washington reports that these fears were overblown, citing a recent Stanford University study. It found that million-dollar income earners are actually less likely to move than Americans earning only average wages; fewer than 2 percent of the tiny fraction of those millionaires who did move cited taxes as a factor.Although I think the article above dismisses too lightly the risk of outmigration of retirees from a small state like New Jersey, there's no better time for a state to raise taxes than when the federal government is lowering taxes.

It's possible that the Fed's actions will end the bull market and this revenue boom may not materialize, but throughout the 1990s the stock market rose despite rate increases, so I would bet on the bull market at this point.

Also, if the mortgage-interest deduction were capped and/or the deduction for state and local taxes were reduced or eliminated, the consequences would be negative for New Jersey.

The second way Trump could help New Jersey's revenue picture is by deregulating Wall Street.

Like large tax cuts, deregularing Wall Street could be disastrous for the economy in the long-run and would definitely exacerbate inequality, but since New Jersey has a large finance industry (180,000+ employees) that contributes a disproportionate share of GDP ($35 billion), since New Jersey has many additional residents who work in finance in New York, and many more residents who don't work in finance still have relatively large capital gains and dividends, it could be good for our short-term budget picture at least.

(New Jerseyans who work in New York pay income taxes to New York State, but they pay taxes on investment income to New Jersey)

(New Jerseyans who work in New York pay income taxes to New York State, but they pay taxes on investment income to New Jersey)

Conclusion

Are these steps right or not? I do not think so. I think the federal government should concentrate on shoring up existing programs, not cutting taxes.

While I would personally welcome the outcome of New Jersey's public sector becoming right-to-work, I do not think fair share fees are unconstitutional. The US Constitution was written decades before anyone had the idea of a union, so ascribing any intention to the Founders regarding unions is impossible. In my opinion, when the Constitution is silent, the legislation is (usually) constitutional.

BUT if there is a stock market rally and Wall Street grows disproportionately to the rest of the economy, the state will have more money that it could spend on state aid. If Abood is overturned, the NJEA is disempowered, and teacher salaries and benefits start to increase more slowly, NJ school districts will be in a different place budgetarily and education policy-making will shift dramatically.

(Of course, overturning Abood isn't the only decision the US Supreme Court will make regarding education. It's just the one I focused on because this blog is on NJ education aid and fiscal policy.)

This article looks at some other major education-related cases that are in progress.

Are these steps right or not? I do not think so. I think the federal government should concentrate on shoring up existing programs, not cutting taxes.

While I would personally welcome the outcome of New Jersey's public sector becoming right-to-work, I do not think fair share fees are unconstitutional. The US Constitution was written decades before anyone had the idea of a union, so ascribing any intention to the Founders regarding unions is impossible. In my opinion, when the Constitution is silent, the legislation is (usually) constitutional.

BUT if there is a stock market rally and Wall Street grows disproportionately to the rest of the economy, the state will have more money that it could spend on state aid. If Abood is overturned, the NJEA is disempowered, and teacher salaries and benefits start to increase more slowly, NJ school districts will be in a different place budgetarily and education policy-making will shift dramatically.

---

This article looks at some other major education-related cases that are in progress.

No comments:

Post a Comment